How long will it take for Andromeda to collide with the Milky Way? The time-scale here is the free-fall time, tff . One way of finding this is to assume that Andromeda is on a highly elliptical orbit (\(e \rightarrow 1\)) around the Milky Way. With this assumption, we can use Kepler’s Third Law

\[P^2=\frac{4\pi^2a^3}{G(M_{MW}+M_{And})}\]

where P is the period of the orbit and a is the semi-major axis. How does free fall time relate to the period? Estimate it to an order of magnitude.

We already have our equation, but we need to modify it sightly. Normally the period of an orbit is the length of time needed for the orbiting body to complete one full orbit. Since we are assuming a highly elliptical orbit that ends in collision, we only need half of an orbit.

\[P^2=\frac{4\pi^2a^3}{G(M_{MW}+M_{And})}\]

\[P=\left(\frac{4\pi^2a^3}{G(M_{MW}+M_{And})}\right)^{\frac{1}{2}}\]

\[T_{ff}=\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)\left(\frac{4\pi^2a^3}{G(M_{MW}+M_{And})}\right)^{\frac{1}{2}}\]

Now let's plug in numbers:

\[T_{ff}=\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)\left(\frac{4\pi^2(2.4\times 10^{24} cm)^3}{(6.67\times 10^{-8}cm^3 g^{-1}s^{-2})(1.6\times 10^{45}g+3\times10^{45}g)}\right)^{\frac{1}{2}}\]

\[\boxed{T_{ff}=7\times 10^{17} sec \approx 4\text{ billion years}}\]

Let’s estimate the average number density of stars throughout the Milky Way, n. First, we need to clarify the distribution of stars. Stars are concentrated in the center of the galaxy, and their density decreases exponentially:

\[n(r)\propto e^{-r/R_s}\]

Rs is also known as the “scale radius” of the galaxy. The Milky Way has a scale radius of 3.5 kpc.

With this in mind, estimate n in two ways:

(a) Consider that within a 2 pc radius of the Sun there are five stars: the Sun, α Centauri A and B, Proxima Centauri, and Barnard’s Star.

So, we have a small sample, but we can work with it.

\[n=\frac{stars}{volume}\]

A radius around the sun is a sphere, so \(V=\frac{4}{3}\pi r^3\).

\[n=\frac{stars}{\frac{4}{3}\pi r^3}\]

One parsec is \(3\times 10^{18} cm\) so 2 parsecs is \(6\times 10^{18} cm\). We have 5 stars in this radius.

\[n=\frac{5\text{ stars}}{\frac{4}{3}\pi (6\times 10^{18}cm)^3}\]

\[\boxed{n=5.5\times 10^{-57} \frac{stars}{cm^3}}\]

(b) The Galaxy’s “scale height” is 330 pc. Use the galaxy’s scale lengths as the lengths of the volume within the Galaxy containing most of the stars. Assume a typical stellar mass of 0.5M.

In this part, we are approximating the galaxy as a cylinder of radius \(R_s\) and height 330 pc. We can then use the total solar mass of the galaxy and the average solar mass to find out the total density of stars.

\[n=\frac{stars}{volume}\]

\[V=\pi R_s^2 h\]

\[stars=\frac{M_{galaxy}}{M_*}\]

\[n=\frac{\frac{M_{galaxy}}{M_*}}{\pi R_s^2 h}\]

330 pc is about \(10^{21} cm\), and 3.5kpc is about \(10^{22}cm\), so:

\[n=\frac{\frac{10^{10}M_*}{0.5M_*}}{\pi (10^{22}cm)^2 (10^{21}cm)}\]

\[\boxed{n=6.3\times 10^{-55} \frac{stars}{cm^3}}\]

Determine the collision rate of the stars using the number density of the stars (n), the cross-section for a star σ ̊, and the average velocity of Milkomeda’s stars as they collide v.

For this part, we will use a mechanism known as dimensional analysis to get an approximation for a complicated process.

We want to solve for the collision rate \(C\) in \(\frac{1}{time}\).

We know Stellar Density \(n=\frac{stars}{length^3}\), galactic velocity \(v=\frac{length}{time}\), and stellar cross section \(\sigma = \frac{length^2}{star}\)

Conveniently, the units of \(nv\sigma=\left(\frac{stars}{length^3}\right)\left(\frac{length}{time}\right)\left(\frac{length^2}{star}\right)=\frac{1}{time}=C\)

This means that:

\[C= nv\sigma\]

(Technically the equals sign should be a proportionate sign since dimensional analysis doesn't include coefficients, but we will ignore this for our rough approximation).

Let's break down our variables.

\(n\) is stellar density, which we solved for above. Thus \(n=6.3\times 10^{-55}\frac{stars}{cm^3}\).

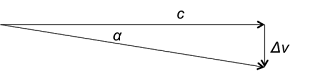

\(v\) is galactic velocity, which Wikipedia claims right now is about \(1\times 10^7 cm/sec\). However, when the galaxies collide this will be much greater due to gravitational acceleration. We can use conservation of energy to find this. Let\(M_{MW}\) and \(M_{And}\) be the masses of the two galaxies, \(U\) be gravity potential energy, and \(a\) be their current separation.

\[U=\frac{GM_{MW}M_{And}}{a}\]

This energy will be converted to kinetic energy at the time of collision, so:

\[\frac{GM_{MW}M_{And}}{a}=\frac{1}{2}(M_{MW}+M_{And})v_1^2\]

Thus:

\[v=v_0+\left(\frac{2GM_{MW}M_{And}}{(M_{MW}+M_{And})a}\right)^{\frac{1}{2}}\]

\[v=1\times 10^7cm/s+\left(\frac{2(6.7\times 10^{-8}cm^3g^{-1}s^{-2})(1.6\times 10^{45}g \times 3\times 10^{45}g)}{(1.6\times 10^{45}g+3\times 10^{45}g)(2.4\times 10^{24}cm)}\right)^{\frac{1}{2}}\]

\[v=1.8\times 10^7cm/s\]

\(\sigma\) is the cross sectional area of a star. If we assume that a star's radius is \(7\times 10^{10}cm\), then \(\sigma=\pi (7\times 10^{10})^2=1.5\times 10^{22}cm^2\)

It's time to put this all together:

\[C= nv\sigma=(6.3\times 10^{-55}stars/cm^3)(1.8\times 10^7 cm/s)(1.5\times 10^{22}cm^2/star)\]

\[\boxed{C=1.7\times 10^{-25} collisions/sec}\]

How many stars will collide every year? Is the Sun safe, or likely to collide with another star?

This is about \(5.3\times 10^{-18}\) collisions per year.

If we invert this to find how long it would take for a single collision, we find that a collision will occur once every \(1.9\times 10^{17} years\). This equates to pretty much never.

The sun is very safe.

I worked with M. Bledsoe, B. Brzycki, G. Grell, and N. James on these problems.