Consider a photon that has just been created via a nuclear reaction in the center of the Sun. The photon now starts a long and arduous journey to the Earth to be enjoyed by Ay16 students studying

on a nice Spring day.

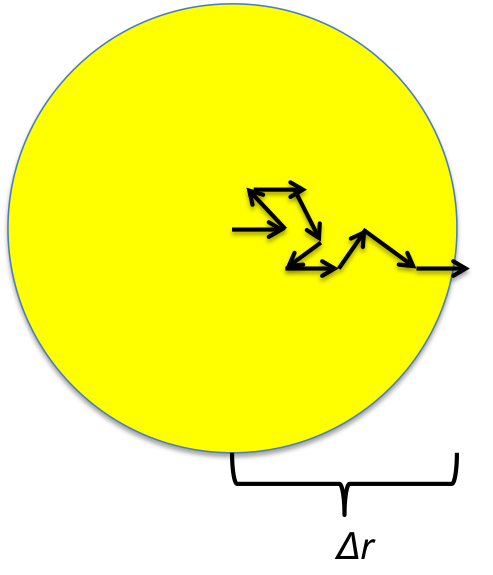

(a) The photon does not travel freely from the Sun’s center to the surface. Instead it random walks, one collision at a time. Each step of the random walk traverses an average distance l, also known as the mean free path. On average, how many steps does the photon take to travel a distance ∆r?

(a) The photon does not travel freely from the Sun’s center to the surface. Instead it random walks, one collision at a time. Each step of the random walk traverses an average distance l, also known as the mean free path. On average, how many steps does the photon take to travel a distance ∆r?

(b) What is the photon’s average velocity over the total displacement after many steps? Call this ⃗vdiff, the diffusion velocity.

(c) The “mean free path” l is the characteristic (i.e. average) distance between collisions. Consider a photon moving through a cloud of electrons with a number density n. Each electron presents an effective cross-section σ. Give an analytic expression for “mean free path” relating these parameters.

(d) The mean free path l can also be related to the mass density of absorbers ρ, and the “absorp- tion coefficient” κ (cross-sectional area of absorbers per unit mass). How is κ related to σ? Express vdiff in terms of κ and ρ using dimensional analysis.

(e) What is the diffusion timescale for a photon moving from the center of the sun to the surface? The cross section for electron scattering is σT = 7 x 1025 cm2 and you can assume pure hydrogen for the Sun’s interior. Be careful about the mass of material through which the photon travels, not just the things it scatters off of. Assume a constant density, ρ, set equal to the mean Solar density (N.B.: the subscript T is for Thomson. The scattering of photons by free (i.e. ionized) electrons where both the K.E. of the electron and λ of the photon remain constant—i.e. an elastic collision—is called Thomson scattering, and is a low-energy process appropriate if the electrons aren’t moving too fast, which is the case in the Sun.)

Let's get to it.

(a) The photon does not travel freely from the Sun’s center to the surface. Instead it random walks, one collision at a time. Each step of the random walk traverses an average distance l, also known as the mean free path. On average, how many steps does the photon take to travel a distance ∆r?

It's time for some math trickery. If we just sum up a random path, we should always get zero if there are enough steps, so we need to be crafty. Let's square everything, then take the square root of it all afterwards.

\[\Delta \vec{r}^2 = (\sum \vec{l})^2\]

\[\Delta \vec{r}^2 = (\vec{l}_1+\vec{l}_2+...+\vec{l}_n)^2\]

(c) The “mean free path” l is the characteristic (i.e. average) distance between collisions. Consider a photon moving through a cloud of electrons with a number density n. Each electron presents an effective cross-section σ. Give an analytic expression for “mean free path” relating these parameters.

(d) The mean free path l can also be related to the mass density of absorbers ρ, and the “absorp- tion coefficient” κ (cross-sectional area of absorbers per unit mass). How is κ related to σ? Express vdiff in terms of κ and ρ using dimensional analysis.

(e) What is the diffusion timescale for a photon moving from the center of the sun to the surface? The cross section for electron scattering is σT = 7 x 1025 cm2 and you can assume pure hydrogen for the Sun’s interior. Be careful about the mass of material through which the photon travels, not just the things it scatters off of. Assume a constant density, ρ, set equal to the mean Solar density (N.B.: the subscript T is for Thomson. The scattering of photons by free (i.e. ionized) electrons where both the K.E. of the electron and λ of the photon remain constant—i.e. an elastic collision—is called Thomson scattering, and is a low-energy process appropriate if the electrons aren’t moving too fast, which is the case in the Sun.)

Let's get to it.

(a) The photon does not travel freely from the Sun’s center to the surface. Instead it random walks, one collision at a time. Each step of the random walk traverses an average distance l, also known as the mean free path. On average, how many steps does the photon take to travel a distance ∆r?

It's time for some math trickery. If we just sum up a random path, we should always get zero if there are enough steps, so we need to be crafty. Let's square everything, then take the square root of it all afterwards.

\[\Delta \vec{r}^2 = (\sum \vec{l})^2\]

\[\Delta \vec{r}^2 = (\vec{l}_1+\vec{l}_2+...+\vec{l}_n)^2\]

Since we are multiplying vectors, we use the dot product.

\[\Delta \vec{r}^2 = (\sum |\vec{l}|^2cos(0))+(\text{dot products of non-equal vectors})\]

Since the dot products of non-equal vectors will have cosine values every distributed from -1 to 1, they can be ignored as their sum approaches 0.

\[\Delta \vec{r}^2 = \sum |\vec{l}|^2\]

Now let's let \(N\) equal the number of steps.

\[\Delta \vec{r}^2 = N\times l^2\]

\[\boxed{\Delta \vec{r} = l \sqrt{N}}\]

Now let's let \(N\) equal the number of steps.

\[\Delta \vec{r}^2 = N\times l^2\]

\[\boxed{\Delta \vec{r} = l \sqrt{N}}\]

(b) What is the photon’s average velocity over the total displacement after many steps? Call this ⃗vdiff the diffusion velocity.

Let's think critically on this. All photons travel at the speed of light, \(c\), so the time to cover a straight-line distance is \(\frac{d}{c}\). We can use this.

\[\vec{v_{diff}}=\frac{\Delta \vec{r}}{t}\]

\[\vec{v_{diff}}=\frac{l \sqrt{N}}{t}\]

\(t\) is the time it takes for the light to travel the total distance \(l\), so \(t=\frac{lN}{c}\).

\[\vec{v_{diff}}=\frac{l \sqrt{N}}{\frac{lN}{c}}\]

\[\boxed{\vec{v_{diff}}=\frac{c}{\sqrt{N}}}\]

(c) The “mean free path” l is the characteristic (i.e. average) distance between collisions. Consider a photon moving through a cloud of electrons with a number density n. Each electron presents an effective cross-section σ. Give an analytic expression for “mean free path” relating these parameters.

Let's use dimensional analysis to solve this.

We know that \(\sigma = \frac{length^2}{item}\), and \(n=\frac{items}{length^3}\). We need these variables to equal \(l=length\).

\[length = \frac{item}{length^2} \times \frac{length^3}{items}=\boxed{l=\frac{1}{n\sigma}}\]

(d) The mean free path l can also be related to the mass density of absorbers ρ, and the “absorp- tion coefficient” κ (cross-sectional area of absorbers per unit mass). How is κ related to σ? Express vdiff in terms of κ and ρ using dimensional analysis.

Let's do this again.

\(\kappa = \frac{length^2}{mass}\), \(c=\frac{length}{time}\), \(\Delta \vec{r}=length\), and \(\rho=\frac{mass}{length^3}\). We need these variables to equal \(v=\frac{length}{time}\).

\[\frac{length}{time} = \frac{mass}{length^2}\times\frac{length^3}{mass} \times \frac{1}{length} \times\frac{length}{time}=\boxed{\vec{v_{diff}}=\frac{c}{\Delta\vec{r}\kappa\rho}}\]

(e) What is the diffusion timescale for a photon moving from the center of the sun to the surface? The cross section for electron scattering is σT = 7 x 10-25 cm2 and you can assume pure hydrogen for the Sun’s interior. Be careful about the mass of material through which the photon travels, not just the things it scatters off of. Assume a constant density, ρ, set equal to the mean Solar density.

This is pretty straightforward.

We already know that \(\vec{v_{diff}}=\frac{c}{\Delta\vec{r}\kappa\rho}\), so we just need to use this velocity to solve for time. We know that \(v=\frac{\Delta \vec{r}}{t}\) so:

\[t=\frac{\Delta \vec{r}^2 \kappa \rho}{c}\]

\(\kappa=\frac{\sigma}{M_H}\) where \(M_H\) is the mass of a hydrogen atom.

\[t=\frac{\Delta \vec{r}^2 \kappa \rho}{c}\]

\(\kappa=\frac{\sigma}{M_H}\) where \(M_H\) is the mass of a hydrogen atom.

\[t=\frac{\Delta \vec{r}^2 \sigma \rho}{cM_H}\]

\(\sigma=7\times 10^{-25}cm^2\)

\(M_H=1.67\times10^{-24}g\)

\(\Delta\vec{r}=7\times 10^{10}cm\)

\(\rho=1.41g/cm^3\)

\(c=3\times 10^{10}cm/s\)

\[t=\frac{(7\times 10^{10} cm)^2 \times (7 \times 10^{-25} cm^2) \times (1.41g/cm^3)}{(3\times10^{10}cm/s) \times (1.67 \times 10^{-24}g)}=1\times10^11sec = \boxed{3000\text{ years}}\]

\(\sigma=7\times 10^{-25}cm^2\)

\(M_H=1.67\times10^{-24}g\)

\(\Delta\vec{r}=7\times 10^{10}cm\)

\(\rho=1.41g/cm^3\)

\(c=3\times 10^{10}cm/s\)

\[t=\frac{(7\times 10^{10} cm)^2 \times (7 \times 10^{-25} cm^2) \times (1.41g/cm^3)}{(3\times10^{10}cm/s) \times (1.67 \times 10^{-24}g)}=1\times10^11sec = \boxed{3000\text{ years}}\]

I worked with G. Grell and S. Morrison on this problem.

Good! I think the real value is more like 50,000 years, but you were only off by an order of magnitude so that seems reasonable.

ReplyDelete