Over spring break I acquired my first motorcycle, a 2015 BMW F800R.

(Photo from BMW)

This beauty is powered by a 800cc parallel twin engine that outputs 90 hp (66 kW) at 8,000 RPM's and 63 lb-ft (86 Nm) of torque at 5,800 RPM's. Surprisingly, the engine still gets a reported 60 mpg. I have not had the chance to ride her yet, as I will not have my license until May, but we left her in the care of the dealership for a May pick up date.

This bike falls into the category of "naked bikes" or "streetfighters." Originally this category consisted of sport/racing bikes that owners had modified by removing the plastic fairings and windshield to create an aggressive-looking, lightweight, and high performance motorcycle designed to rule the urban jungle. After gaining popularity, manufacturers began to design these bikes intentionally eventually evolving them into the category that we know today. These bikes are not designed for long trips due to their lack of windscreen and semi-egressive (weight forward) riding position. They hit their prime in the urban jungle or on twisty backroads where their lightweight and superb handling shines.

The F800R goes 0-60mph in about 3.5 seconds (equivalent to a Ferrari California T) and a top speed of about 130mph. Of course, despite these performance specs, safe riding always comes first.

This is going to be a really fun summer.

(Photo from BMW)

Sunday, March 29, 2015

Worksheet 11.2, Problem 1: Stellar Energy Flow

Stars generate their energy in their cores, where nuclear fusion is taking place. The energy generated is eventually radiated out at the star’s surface. Therefore, there exists a gradient in energy density from the center (high) to the surface (low), but thermodynamic systems tend towards ‘equilibrium.’ In the following sections we will determine how energy flows through the star.

(a) Inside the star, consider a mass shell of width ∆r, at a radius r. This mass shell has an energy density u + ∆u, and the next mass shell out (at radius r + ∆r) will have an energy density u. Both shells behave as blackbodies.

The net outwards flow of energy, L(r), must equal the total excess energy in the inner shell divided by the amount of time needed to cross the shell’s width ∆r. Use this to derive an expression for L(r) in terms of \(\frac{du}{dr}\), the energy density profile. This is the diffusion equation describing the outward flow of energy.

(b) From the diffusion equation, use the fact that the energy density of a blackbody is u(T(r))=aT4 to derive the differential equation:

\(\frac{dT(r)}{dr} \propto -\frac{L(r)\kappa \rho(r)}{\pi r^2 a c T^3}\)

where a is the radiation constant. You just derived the equation for radiative energy transport!

(a) Inside the star, consider a mass shell of width ∆r, at a radius r. This mass shell has an energy density u + ∆u, and the next mass shell out (at radius r + ∆r) will have an energy density u. Both shells behave as blackbodies.

The net outwards flow of energy, L(r), must equal the total excess energy in the inner shell divided by the amount of time needed to cross the shell’s width ∆r. Use this to derive an expression for L(r) in terms of \(\frac{du}{dr}\), the energy density profile. This is the diffusion equation describing the outward flow of energy.

The net outwards flow of energy, L(r), must equal the total excess energy in the inner shell divided by the amount of time needed to cross the shell’s width ∆r. Use this to derive an expression for L(r) in terms of \(\frac{du}{dr}\), the energy density profile. This is the diffusion equation describing the outward flow of energy.

Let's start by finding the energy in a shell. Since a shell is hollow sphere with thickness \(\Delta r\), the energy in the shell is volume times energy density.

\[E=4\pi r^2 \Delta r \Delta u\]

In order to find L(r), we need to divide by the time it takes for a photon to reach the given shell.

\[v_{diff}=\frac{\Delta r}{t}=\frac{lc}{\Delta r}\]

\[t=\frac{\Delta r^2}{lc}\]

\[L(r)=\frac{E}{t}=\frac{4\pi r^2cl\Delta u \Delta r}{\Delta r^2}=4\pi r^2 cl \frac{du}{dr}\]

\[\boxed{L(r)=4\pi r^2 cl \frac{du}{dr}}\]

(b) From the diffusion equation, use the fact that the energy density of a blackbody is u(T(r))=aT4 to derive the differential equation:

\(\frac{dT(r)}{dr} \propto -\frac{L(r)\kappa \rho(r)}{\pi r^2 a c T^3}\)

where a is the radiation constant. You just derived the equation for radiative energy transport!

\(\frac{dT(r)}{dr} \propto -\frac{L(r)\kappa \rho(r)}{\pi r^2 a c T^3}\)

where a is the radiation constant. You just derived the equation for radiative energy transport!

Let's start by differentiating the energy density equation with respect to T.

\[u(T(r))=aT^4\]

\[du=4aT^3dT(r)\]

The rest is simple. We just substitute \(du\) into our original equation and ignore any coefficients.

\[L(r)=4\pi r^2 cl \frac{du}{dr}\]

\[L(r)=4\pi r^2 cl \frac{4aT^3dT(r)}{dr}\]

\[L(r) \propto \frac{\pi r^2 claT^3dT(r)}{dr}\]

We know that \(l=\frac{1}{\kappa \rho (r)}, suo substituting this gives us:

\[L(r) \propto \frac{\pi r^2 caT^3dT(r)}{\kappa \rho (r) dr}\]

Lastly, we can solve for \(\frac{dT(r)}{dr}\).

\[\boxed{\frac{dt(r)}{dr} \propto -\frac{L(r)\kappa \rho (r)}{\pi r^2 a c T^3}}\]

I worked with G. Grell and S. Morrison to solve this problem.

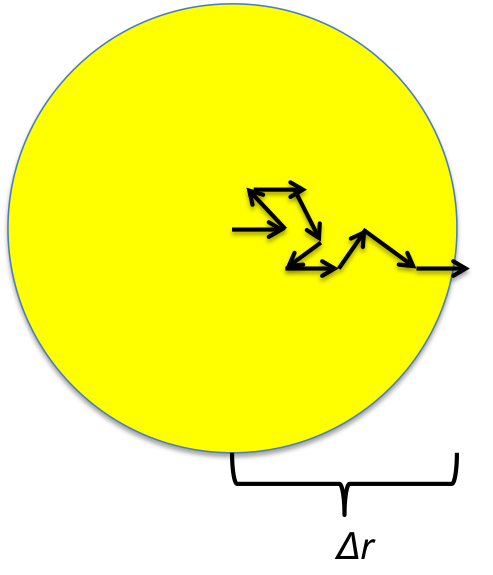

Worksheet 11.1, Problem 1: Photons Random Walking Out of a Star

Consider a photon that has just been created via a nuclear reaction in the center of the Sun. The photon now starts a long and arduous journey to the Earth to be enjoyed by Ay16 students studying

on a nice Spring day.

(a) The photon does not travel freely from the Sun’s center to the surface. Instead it random walks, one collision at a time. Each step of the random walk traverses an average distance l, also known as the mean free path. On average, how many steps does the photon take to travel a distance ∆r?

(a) The photon does not travel freely from the Sun’s center to the surface. Instead it random walks, one collision at a time. Each step of the random walk traverses an average distance l, also known as the mean free path. On average, how many steps does the photon take to travel a distance ∆r?

(b) What is the photon’s average velocity over the total displacement after many steps? Call this ⃗vdiff, the diffusion velocity.

(c) The “mean free path” l is the characteristic (i.e. average) distance between collisions. Consider a photon moving through a cloud of electrons with a number density n. Each electron presents an effective cross-section σ. Give an analytic expression for “mean free path” relating these parameters.

(d) The mean free path l can also be related to the mass density of absorbers ρ, and the “absorp- tion coefficient” κ (cross-sectional area of absorbers per unit mass). How is κ related to σ? Express vdiff in terms of κ and ρ using dimensional analysis.

(e) What is the diffusion timescale for a photon moving from the center of the sun to the surface? The cross section for electron scattering is σT = 7 x 1025 cm2 and you can assume pure hydrogen for the Sun’s interior. Be careful about the mass of material through which the photon travels, not just the things it scatters off of. Assume a constant density, ρ, set equal to the mean Solar density (N.B.: the subscript T is for Thomson. The scattering of photons by free (i.e. ionized) electrons where both the K.E. of the electron and λ of the photon remain constant—i.e. an elastic collision—is called Thomson scattering, and is a low-energy process appropriate if the electrons aren’t moving too fast, which is the case in the Sun.)

Let's get to it.

(a) The photon does not travel freely from the Sun’s center to the surface. Instead it random walks, one collision at a time. Each step of the random walk traverses an average distance l, also known as the mean free path. On average, how many steps does the photon take to travel a distance ∆r?

It's time for some math trickery. If we just sum up a random path, we should always get zero if there are enough steps, so we need to be crafty. Let's square everything, then take the square root of it all afterwards.

\[\Delta \vec{r}^2 = (\sum \vec{l})^2\]

\[\Delta \vec{r}^2 = (\vec{l}_1+\vec{l}_2+...+\vec{l}_n)^2\]

(c) The “mean free path” l is the characteristic (i.e. average) distance between collisions. Consider a photon moving through a cloud of electrons with a number density n. Each electron presents an effective cross-section σ. Give an analytic expression for “mean free path” relating these parameters.

(d) The mean free path l can also be related to the mass density of absorbers ρ, and the “absorp- tion coefficient” κ (cross-sectional area of absorbers per unit mass). How is κ related to σ? Express vdiff in terms of κ and ρ using dimensional analysis.

(e) What is the diffusion timescale for a photon moving from the center of the sun to the surface? The cross section for electron scattering is σT = 7 x 1025 cm2 and you can assume pure hydrogen for the Sun’s interior. Be careful about the mass of material through which the photon travels, not just the things it scatters off of. Assume a constant density, ρ, set equal to the mean Solar density (N.B.: the subscript T is for Thomson. The scattering of photons by free (i.e. ionized) electrons where both the K.E. of the electron and λ of the photon remain constant—i.e. an elastic collision—is called Thomson scattering, and is a low-energy process appropriate if the electrons aren’t moving too fast, which is the case in the Sun.)

Let's get to it.

(a) The photon does not travel freely from the Sun’s center to the surface. Instead it random walks, one collision at a time. Each step of the random walk traverses an average distance l, also known as the mean free path. On average, how many steps does the photon take to travel a distance ∆r?

It's time for some math trickery. If we just sum up a random path, we should always get zero if there are enough steps, so we need to be crafty. Let's square everything, then take the square root of it all afterwards.

\[\Delta \vec{r}^2 = (\sum \vec{l})^2\]

\[\Delta \vec{r}^2 = (\vec{l}_1+\vec{l}_2+...+\vec{l}_n)^2\]

Since we are multiplying vectors, we use the dot product.

\[\Delta \vec{r}^2 = (\sum |\vec{l}|^2cos(0))+(\text{dot products of non-equal vectors})\]

Since the dot products of non-equal vectors will have cosine values every distributed from -1 to 1, they can be ignored as their sum approaches 0.

\[\Delta \vec{r}^2 = \sum |\vec{l}|^2\]

Now let's let \(N\) equal the number of steps.

\[\Delta \vec{r}^2 = N\times l^2\]

\[\boxed{\Delta \vec{r} = l \sqrt{N}}\]

Now let's let \(N\) equal the number of steps.

\[\Delta \vec{r}^2 = N\times l^2\]

\[\boxed{\Delta \vec{r} = l \sqrt{N}}\]

(b) What is the photon’s average velocity over the total displacement after many steps? Call this ⃗vdiff the diffusion velocity.

Let's think critically on this. All photons travel at the speed of light, \(c\), so the time to cover a straight-line distance is \(\frac{d}{c}\). We can use this.

\[\vec{v_{diff}}=\frac{\Delta \vec{r}}{t}\]

\[\vec{v_{diff}}=\frac{l \sqrt{N}}{t}\]

\(t\) is the time it takes for the light to travel the total distance \(l\), so \(t=\frac{lN}{c}\).

\[\vec{v_{diff}}=\frac{l \sqrt{N}}{\frac{lN}{c}}\]

\[\boxed{\vec{v_{diff}}=\frac{c}{\sqrt{N}}}\]

(c) The “mean free path” l is the characteristic (i.e. average) distance between collisions. Consider a photon moving through a cloud of electrons with a number density n. Each electron presents an effective cross-section σ. Give an analytic expression for “mean free path” relating these parameters.

Let's use dimensional analysis to solve this.

We know that \(\sigma = \frac{length^2}{item}\), and \(n=\frac{items}{length^3}\). We need these variables to equal \(l=length\).

\[length = \frac{item}{length^2} \times \frac{length^3}{items}=\boxed{l=\frac{1}{n\sigma}}\]

(d) The mean free path l can also be related to the mass density of absorbers ρ, and the “absorp- tion coefficient” κ (cross-sectional area of absorbers per unit mass). How is κ related to σ? Express vdiff in terms of κ and ρ using dimensional analysis.

Let's do this again.

\(\kappa = \frac{length^2}{mass}\), \(c=\frac{length}{time}\), \(\Delta \vec{r}=length\), and \(\rho=\frac{mass}{length^3}\). We need these variables to equal \(v=\frac{length}{time}\).

\[\frac{length}{time} = \frac{mass}{length^2}\times\frac{length^3}{mass} \times \frac{1}{length} \times\frac{length}{time}=\boxed{\vec{v_{diff}}=\frac{c}{\Delta\vec{r}\kappa\rho}}\]

(e) What is the diffusion timescale for a photon moving from the center of the sun to the surface? The cross section for electron scattering is σT = 7 x 10-25 cm2 and you can assume pure hydrogen for the Sun’s interior. Be careful about the mass of material through which the photon travels, not just the things it scatters off of. Assume a constant density, ρ, set equal to the mean Solar density.

This is pretty straightforward.

We already know that \(\vec{v_{diff}}=\frac{c}{\Delta\vec{r}\kappa\rho}\), so we just need to use this velocity to solve for time. We know that \(v=\frac{\Delta \vec{r}}{t}\) so:

\[t=\frac{\Delta \vec{r}^2 \kappa \rho}{c}\]

\(\kappa=\frac{\sigma}{M_H}\) where \(M_H\) is the mass of a hydrogen atom.

\[t=\frac{\Delta \vec{r}^2 \kappa \rho}{c}\]

\(\kappa=\frac{\sigma}{M_H}\) where \(M_H\) is the mass of a hydrogen atom.

\[t=\frac{\Delta \vec{r}^2 \sigma \rho}{cM_H}\]

\(\sigma=7\times 10^{-25}cm^2\)

\(M_H=1.67\times10^{-24}g\)

\(\Delta\vec{r}=7\times 10^{10}cm\)

\(\rho=1.41g/cm^3\)

\(c=3\times 10^{10}cm/s\)

\[t=\frac{(7\times 10^{10} cm)^2 \times (7 \times 10^{-25} cm^2) \times (1.41g/cm^3)}{(3\times10^{10}cm/s) \times (1.67 \times 10^{-24}g)}=1\times10^11sec = \boxed{3000\text{ years}}\]

\(\sigma=7\times 10^{-25}cm^2\)

\(M_H=1.67\times10^{-24}g\)

\(\Delta\vec{r}=7\times 10^{10}cm\)

\(\rho=1.41g/cm^3\)

\(c=3\times 10^{10}cm/s\)

\[t=\frac{(7\times 10^{10} cm)^2 \times (7 \times 10^{-25} cm^2) \times (1.41g/cm^3)}{(3\times10^{10}cm/s) \times (1.67 \times 10^{-24}g)}=1\times10^11sec = \boxed{3000\text{ years}}\]

I worked with G. Grell and S. Morrison on this problem.

Sunday, March 22, 2015

Day Lab: Summary and Analysis

The ultimate goal of the day lab was to observationally calculate the distance from the Earth to the Sun, or the Astronomical Unit (AU). In the three parts of the lab, we found the velocity of each side of the sun relative to Earth, the rotational period of the sun, and the "orbital" angular velocity of the sun. We can use these three measurements to calculate the AU.

\(P_{Orbit}\) is orbital period

\(P_{Rotation}\) is rotational period

\(\omega_{Orbit}\) is orbital angular velocity

\(R\) is solar radius

\(AU\) is the Astronomical Unit

\(\theta\) is the sun's angular diameter

\(V\) is rotational velocity of a particle of the sun

Let's get started. First we can find the solar radius.

\[V=\frac{2\pi R}{P_{Rot}}\]

\[R=\frac{V \times P_{Rot}}{2 \pi}=\frac{1.75 km/s \times 24.92 days}{2\pi}=\boxed{6\times 10^{10} cm}\]

Now that we know the solar radius, we can find the AU using the sun's angular diameter and some trigonometry.

\[sin(\theta)=\frac{2R}{AU}\]

For small angles, \(sin(\theta) \approx \theta\), so:

\[\theta \approx \frac{2R}{AU}\]

\(P_{Orbit}\) is orbital period

\(P_{Rotation}\) is rotational period

\(\omega_{Orbit}\) is orbital angular velocity

\(R\) is solar radius

\(AU\) is the Astronomical Unit

\(\theta\) is the sun's angular diameter

\(V\) is rotational velocity of a particle of the sun

Let's get started. First we can find the solar radius.

\[V=\frac{2\pi R}{P_{Rot}}\]

\[R=\frac{V \times P_{Rot}}{2 \pi}=\frac{1.75 km/s \times 24.92 days}{2\pi}=\boxed{6\times 10^{10} cm}\]

Now that we know the solar radius, we can find the AU using the sun's angular diameter and some trigonometry.

\[sin(\theta)=\frac{2R}{AU}\]

For small angles, \(sin(\theta) \approx \theta\), so:

\[\theta \approx \frac{2R}{AU}\]

\[AU=\frac{2R}{\theta}=\frac{2\times (6\times 10^{10}cm)}{0.55^{\circ}}=\boxed{1.25 \times 10^{13} cm}\]

I estimate the uncertainty of this value to be \(\pm 5\times 10^{12} cm\) because all of our calculations were performed to about 2 significant figures, and no experiment seemed like it could introduce an extremely skewing amount of error.

The actual measure of the AU is \(1.50\times 10^{13} cm\), placing our calculation only \(2.5 \times 10^{12} cm\) off. This equates to about 17% error.

This error could be introduced by relatively crude means of tracking sunspots on a grid overlay using a marker, (not the highest degree of accuracy), inexact measurement of the time it took the sun to pass through it's diameter (we stopped the time when it looked like it had fully crossed a line), or our spectral data could be skewed from dust on the CCD or unforeseen alternate light sources.

This experiment was conducted with the Tuesday at 1:00PM lab group.

Day Lab Part 3: Determine the Rotational Period of the Sun

Usually, in this part of the experiment, we would observe a sunspot's movement in order to calculate the rotational period of the sun. Unfortunately, at the time of data collection, there were no visible sunspots. Legacy data was used on the computer in order to salvage this part of the lab.

By overlaying longitude and latitude lines on a digital image of the sun, we were able to track the movement of the sunspots over time by moving ahead in the legacy data. By recording the angular distance and time for each sunspot, we made use of the relation:

\[P=\frac{360^{\circ} \times t}{\theta}\]

Where \(P\) is period, \(t\) is time, and \(\theta\) is rotation angle.

\[P=\frac{360^{\circ} \times 7975min}{80^{\circ}}=35,890min=\boxed{24.92days}\]

This experiment was conducted with the Tuesday 1:00PM Lab Group.

|

| http://www.astro.virginia.edu/class/majewski/astr130/LECTURES/LECTURE6/sunspots.gif |

\[P=\frac{360^{\circ} \times t}{\theta}\]

Where \(P\) is period, \(t\) is time, and \(\theta\) is rotation angle.

\[P=\frac{360^{\circ} \times 7975min}{80^{\circ}}=35,890min=\boxed{24.92days}\]

This experiment was conducted with the Tuesday 1:00PM Lab Group.

Friday, March 20, 2015

Day Lab Part 2: Determine the Rotational Speed of the Sun

This is the most intensive part of the lab procedure. In doing this, we are measuring the rotational speed of the sun using the doppler effect.

In a nutshell, the Doppler Effect states that waves emitted from an object moving towards an observer will have a higher frequency and correspondingly lower wavelength. Inversely, waves emitted from an object moving away from an observer will have a lower frequency and correspondingly higher wavelength. This is the classic "siren drive by" effect where the pitch lowers after the police car passes you.

Since the sun is rotating about some axis, by measuring the light spectrum from the sun emitted by the different edges of it, different edges will have different doppler shifts based on weather they are moving towards or away from the Earth.

Since we do not know which way the sun is rotating, we took measurements at all of the X's below. The diagram also features a ridiculously exaggerated doppler effect that assumes blindly that the sun rotates from left to right.

Using a CCD camera and a spectrograph, we were able to take pictures of the visible spectrum of sunlight. We used two sodium emission lines from he sun as our chosen wavelengths in which we would measure doppler shifts, and used an unchanging water line from the atmosphere as a reference point to measure said shifts.

We then used a computational Excel spreadsheet to analyze the spectral data to find the peak values for the sodium lines of each measurement spectrum. From there, we found the lines that had the greatest spectral difference: the left and right, which makes the above diagram accurate. We found that the two lines were about 3.9 pixels apart. After running conversion factors to translate this into actual wavelengths, we determined that there was a net doppler shift of 0.07 angstroms in wavelength between the two measured points. applying further conversions, we found that these points differ in velocity by 1.75 km/s.

I worked with the Tuesday 1:00PM lab group to perform this experiment.

In a nutshell, the Doppler Effect states that waves emitted from an object moving towards an observer will have a higher frequency and correspondingly lower wavelength. Inversely, waves emitted from an object moving away from an observer will have a lower frequency and correspondingly higher wavelength. This is the classic "siren drive by" effect where the pitch lowers after the police car passes you.

Since the sun is rotating about some axis, by measuring the light spectrum from the sun emitted by the different edges of it, different edges will have different doppler shifts based on weather they are moving towards or away from the Earth.

Since we do not know which way the sun is rotating, we took measurements at all of the X's below. The diagram also features a ridiculously exaggerated doppler effect that assumes blindly that the sun rotates from left to right.

Using a CCD camera and a spectrograph, we were able to take pictures of the visible spectrum of sunlight. We used two sodium emission lines from he sun as our chosen wavelengths in which we would measure doppler shifts, and used an unchanging water line from the atmosphere as a reference point to measure said shifts.

We then used a computational Excel spreadsheet to analyze the spectral data to find the peak values for the sodium lines of each measurement spectrum. From there, we found the lines that had the greatest spectral difference: the left and right, which makes the above diagram accurate. We found that the two lines were about 3.9 pixels apart. After running conversion factors to translate this into actual wavelengths, we determined that there was a net doppler shift of 0.07 angstroms in wavelength between the two measured points. applying further conversions, we found that these points differ in velocity by 1.75 km/s.

I worked with the Tuesday 1:00PM lab group to perform this experiment.

Day Lab Part 1: Determine the Angular Size of the Sun

We can measure the sun's angular diameter by recording the time that it takes the sun to move through its own diameter. We can do this by marking the two edges of the sum on a piece of paper after focusing the sun through a lens, and measuring the time that it takes for the sun to move entirely across the line.

It's time to do some math.

There are 24 hours in a day, so the sun moves through 360 degrees in 24 hours.

\[\frac{t_{diameter}}{\theta_{diameter}}=\frac{t_{orbit}}{\theta_{orbit}}\]

\[\theta_{diameter}=\frac{t_{diameter}\times \theta_{orbit}}{t_{orbit}}\]

\[\theta_{diameter}=\frac{2:11.14 \times 360^{\circ} }{24:00:00}\]

\[\theta_{diameter}=\boxed{0.55^{\circ}} \]

Therefore, the angular diameter of the sun as viewed form Earth or 1 AU, is 0.55 degrees.

I worked with the Tuesday 1:00PM lab group to do this experiment.

Sunday, March 8, 2015

Zwicky: "Dark Matter in the Coma Cluster"

In 1933, Fritz Zwicky wrote a paper on the evidence for Dark Matter in the Coma Cluster.

Firstly, what is the Coma Cluster?

The Coma Cluster, pictured below, is a galactic cluster of over 1000 galaxies located in the same region of the sky as the constellation Coma Berenices. For all practical purposes, this acts a large group distributed particles, something that we and Zwicky can apply Virial Theorem to.

Zwicky starts by stating the viral theorem that we know as:

\[2K=-U\]

Where K is kinetic/thermal energy and U is gravitational energy.

Zwicky then calculates the total mass of the system. He postulates that:

Radius \(R=10^{24}cm\)

Mass of a Nebula \(M_N=10^9M_*\)

1 Solar Mass \(M_*=2\times 10^{33}g\)

There are 800 nebulae in the cluster.

Newton's Gravitational Constant \(G=6.7\times 10^{-8}\frac{cm^3}{gs^2}\)

The average velocity of a component of the system \(v=1.75\times 10^8cm/s\)

Therefore:

\[M=800\times M_N\times M_*=800\times 2\times10^{33}g \times 10^9= \boxed{1.6\times 10^{45}g}\]

This should be the mass of the whole system...

Next let's set up virial theorem.

\[2K=-U\]

We now notice a slight problem, this calculation for mass is about 400 times larger than our calculated observed mass. Something must be missing...

We can see the size of the cluster, so it must be 400 times denser than what we can see. Hence, it must be filled with...

DARK MATTER

Zwicky follows this calculation with a series of other variations of the viral theorem in a futile attempt to account for the missing matter, but he is unable to do so. Thus the answer must be that the coma cluster is filled with...

DARK MATTER

Firstly, what is the Coma Cluster?

The Coma Cluster, pictured below, is a galactic cluster of over 1000 galaxies located in the same region of the sky as the constellation Coma Berenices. For all practical purposes, this acts a large group distributed particles, something that we and Zwicky can apply Virial Theorem to.

|

| http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/7d/Ssc2007-10a1.jpg |

\[2K=-U\]

Where K is kinetic/thermal energy and U is gravitational energy.

Zwicky then calculates the total mass of the system. He postulates that:

Radius \(R=10^{24}cm\)

Mass of a Nebula \(M_N=10^9M_*\)

1 Solar Mass \(M_*=2\times 10^{33}g\)

There are 800 nebulae in the cluster.

Newton's Gravitational Constant \(G=6.7\times 10^{-8}\frac{cm^3}{gs^2}\)

The average velocity of a component of the system \(v=1.75\times 10^8cm/s\)

Therefore:

\[M=800\times M_N\times M_*=800\times 2\times10^{33}g \times 10^9= \boxed{1.6\times 10^{45}g}\]

This should be the mass of the whole system...

Next let's set up virial theorem.

\[2K=-U\]

\[Mv^2=\frac{3GM^2}{5R}\]

\[M=\frac{5v^2R}{3G}=\frac{(1.75\times 10^8cm/s)^2(10^{24}cm)}{6.7\times 10^{-8}\frac{cm^3}{gs^2}}=\boxed{7.6\times 10^{47}g}\]We now notice a slight problem, this calculation for mass is about 400 times larger than our calculated observed mass. Something must be missing...

We can see the size of the cluster, so it must be 400 times denser than what we can see. Hence, it must be filled with...

DARK MATTER

Zwicky follows this calculation with a series of other variations of the viral theorem in a futile attempt to account for the missing matter, but he is unable to do so. Thus the answer must be that the coma cluster is filled with...

DARK MATTER

Worksheet 9, Problem 2: Forming Stars

Forming Stars: Giant molecular clouds occasionally collapse under their own gravity (their own

“weight”) to form stars. This collapse is temporarily held at bay by the internal gas pressure of

the cloud, which can be approximated as an ideal gas such that P=nkT, where n is the number

density (cm ́3) of gas particles within a cloud of mass M comprising particles of mass m ̄ (mostly

hydrogen molecules, H2), and k is the Boltzmann constant, k = 1.4 x 1016erg K-1.

(a) What is the total thermal energy, K, of all of the gas particles in a molecular cloud of total mass M? (HINT: a particle moving in the ith direction has Ethermal =1/2 mv2 =1/2 kT. This fact is a consequence of a useful result called the Equipartition Theorem.)

(b) What is the total gravitational binding energy of the cloud of mass M?

(c) Relate the total thermal energy to the binding energy using the Virial Theorem, recalling that you used something similar to kinetic energy to get the thermal energy earlier.

(a) What is the total thermal energy, K, of all of the gas particles in a molecular cloud of total mass M? (HINT: a particle moving in the ith direction has Ethermal =1/2 mv2 =1/2 kT. This fact is a consequence of a useful result called the Equipartition Theorem.)

(b) What is the total gravitational binding energy of the cloud of mass M?

(c) Relate the total thermal energy to the binding energy using the Virial Theorem, recalling that you used something similar to kinetic energy to get the thermal energy earlier.

(d) If the cloud is stable, then the Viriral Theorem will hold. What happens when the gravitational

binding energy is greater than the thermal (kinetic) energy of the cloud? Assume a cloud of

constant density ρ.

(e) What is the critical mass, MJ , beyond which the cloud collapses? This is known as the “Jeans Mass.”

(f) What is the critical radius, RJ, that the cloud can have before it collapses? This is known as the “Jeans Length.”

(e) What is the critical mass, MJ , beyond which the cloud collapses? This is known as the “Jeans Mass.”

(f) What is the critical radius, RJ, that the cloud can have before it collapses? This is known as the “Jeans Length.”

Let's take it from the top:

a) What is the total thermal energy, K, of all of the gas particles in a molecular cloud of total mass M? (HINT: a particle moving in the ith direction has Ethermal =1/2 mv2 =1/2 kT. This fact is a consequence of a useful result called the Equipartition Theorem.)

This looks pretty easy, but the equation needs a slight modification. Since the terminal energy only accounts for particle movement in 1 direction, we need to multiply it by 3 for our three observable spacial dimensions.

\[K_{particle}=\frac{3}{2}kT\]

Here: k is the Boltzmann Constant and T is the temperature in Kelvin.

We now must sum up all of the particles, so we will use the notation \(M\) to signify the total mass and \(\overline{m}\) to denote the average particle mass.

\[\boxed{K=\frac{3MkT}{2\overline{m}}}\]

(b) What is the total gravitational binding energy of the cloud of mass M?

Okay, this is easy since we derived this on Worksheet 8, Problem 2.

\[\boxed{U=-\frac{GM^2}{R}}\]

(c) Relate the total thermal energy to the binding energy using the Virial Theorem, recalling that you used something similar to kinetic energy to get the thermal energy earlier.

From Worksheet 8 we know that viral theorem states that:

\[2K=-U\]

We have U and we have K, so let's plug and chug.

\[\frac{3MkT}{\overline{m}}=\frac{GM^2}{R}\]

This simplifies to:

\[\boxed{\frac{3kT}{\overline{m}}=\frac{GM}{R}}\]

(d) If the cloud is stable, then the Viriral Theorem will hold. What happens when the gravitational binding energy is greater than the thermal (kinetic) energy of the cloud? Assume a cloud of constant density ρ.

Let's consider this. The kinetic energy exerts a force outward on the cloud which is countered by the gravity potential exerting a gravitational force inwards. So logically, if the gravitational energy is greater than the thermal energy, the cloud will begin to collapse inward due to an unbalanced net inwards force. This is a good thing, because over time, this will form a star!

(e) What is the critical mass, MJ , beyond which the cloud collapses? This is known as the “Jeans Mass.”

When viral theorem holds, the cloud is in equilibrium. Thus if we solve our viral theorem equation for M, we will know that this is the cutoff point for stability.

\[\frac{3kT}{\overline{m}}=\frac{GM}{R}\]

\[\boxed{M_J=\frac{3kTR}{G\overline{m}}}\]

(f) What is the critical radius, RJ, that the cloud can have before it collapses? This is known as the “Jeans Length.”

All that we have to do is rearrange our equation again.

\[\frac{3kT}{\overline{m}}=\frac{GM}{R}\]

\[\boxed{R_J=\frac{GM\overline{m}}{3kT}}\]

This problem done with collaboration with G. Grell, S, Morrison.

Worksheet 9, Problem 2: The Spatial Scale of Star Formation

The size of a modest star forming molecular cloud, like the Taurus region, is about 30 pc. The size of a typical star is, to an order of magnitude, the size of the Sun.

(a) If you let the size of your body represent the size of the star forming complex, how big would the forming stars be? Can you come up with an analogy that would help a layperson understand this difference in scale? For example, if the cloud is the size of a human, then a star is the size of what?

(b) Within the Taurus complex there is roughly 3ˆ104M* of gas. To order of magnitude, what is the average density of the region? What is the average density of a typical star (use the Sun as a model)? How many orders of magnitude difference is this? Consider the difference between lead (ρlead =11.34 g cm ́3) and air (ρair =0.0013 g cm ́3). This is four orders of magnitude, which is a huge difference!

(a) If you let the size of your body represent the size of the star forming complex, how big would the forming stars be? Can you come up with an analogy that would help a layperson understand this difference in scale? For example, if the cloud is the size of a human, then a star is the size of what?

(b) Within the Taurus complex there is roughly 3ˆ104M* of gas. To order of magnitude, what is the average density of the region? What is the average density of a typical star (use the Sun as a model)? How many orders of magnitude difference is this? Consider the difference between lead (ρlead =11.34 g cm ́3) and air (ρair =0.0013 g cm ́3). This is four orders of magnitude, which is a huge difference!

Okay, so let's try to make a comparison as to the size of star forming molecular cloud and an average star.

To do so, we will use a proportion.

\[\frac{d_{star}}{d_{cloud}}=\frac{d_{human}}{d_{?}}\]

\[d_{?}=\frac{d_{human} d_{cloud}}{d_{star}}\]

So the radius of the cloud is 30 pc. A parsec is a unit of distance that corresponds to the distance away an observer must be such that 1 AU (the distance between the Earth and Sun) is angularly 1 arcsecond or about 0.004 degrees. 1 parsec is about 3.26 lightyears, or \(3\times 10^{18}cm\). A human is roughly 100 cm in diameter if we were to curl up into a ball. The sun's diameter is \(1.4\times 10^{11} cm\).

\[d_{?}=\frac{(1\times 10^2 cm)(1.4\times 10^{11}cm)}{9\times 10^{19}cm}=1.6\times 10^{-7}cm\approx \boxed{2nm}\]

So, how big is 2nm exactly? This fantastic website can help: http://htwins.net/scale2/

This site lets us explore all sorts of length scales, from the size of the universe down to the planck length. I encourage you to play with it.

Based off of this site, if a star forming cloud was the size of a human, a star would be the size of a single glucose sugar molecule.

Alternatively, if a star forming cloud was the size of a football field, a star would be the size of a single HIV virus.

Still not comprehendible? Let's keep trying. We are looking for things with a difference in scale of about 10,000,000x.

So, if a star forming cloud was the size of Texas, a star would be the size of a baseball.

Let's do this again for density of the cloud.

\[\rho_{cloud}=\frac{M}{V}=\frac{3\times 10^4M_*}{\frac{4}{3}\pi r^3}=\frac{3\times 10^4 \times 2\times 10^{33}g}{\frac{4}{3}\pi (5\times 10^{19}cm)^3}=\boxed{1\times 10^{-22}\frac{g}{cm^3}}\]

For the sun we get:

\[\rho_{star}=\frac{M}{V}=\frac{M_*}{\frac{4}{3}\pi r^3}=\frac{2\times 10^{33}g}{\frac{4}{3}\pi (7\times 10^{10}cm)^3}=\boxed{1.4\frac{g}{cm^3}}\]

This shows that a star is 10,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 times more dense than a star forming cloud.

This problem done in collaboration with G. Grell and S. Morrison.

For the sun we get:

\[\rho_{star}=\frac{M}{V}=\frac{M_*}{\frac{4}{3}\pi r^3}=\frac{2\times 10^{33}g}{\frac{4}{3}\pi (7\times 10^{10}cm)^3}=\boxed{1.4\frac{g}{cm^3}}\]

This shows that a star is 10,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 times more dense than a star forming cloud.

This problem done in collaboration with G. Grell and S. Morrison.

Saturday, March 7, 2015

Worksheet 8, Problem 2: Total Potential Energy of a Cluster

Consider a spherical distribution of particles, each with a mass mi and a total (collective) mass M, and a total (collective) radius R. Convince yourself that the total potential energy, U,

is approximately \(U\approx -\frac{GM^2}{R}\)

You can derive or look up the actual numerical constant out front. But in general in astronomy, you don’t need this prefactor, which is of order unity.

You can derive or look up the actual numerical constant out front. But in general in astronomy, you don’t need this prefactor, which is of order unity.

\(M\) is the total cluster's mass

\(\rho\) is the density of the cluster

\(R\) is the radius of the cluster

\(r\) is the distance from a particle to the center the cluster

\(G\) is Newton's gravitational constant

\(U\) is the total potential energy of the cluster

Let's begin with an equation for \(U\):

\[dU=-\frac{GMdM}{r}\]

This is the regular gravity potential equation, but because the mass is distributed at different distances from the center of the cluster, it will experience a different gravity potential. Let's find an expression for \(dm\) in terms of \(r\).

Let's slice the cluster into hollow spheres stacked inside one another, each with depth \(dr\). Each slice's mass can be given by:

\[dM=4\pi r^2\rho dr\]

This makes sense, since each has a depth \(dr\) and its length and width are given by the surface area of the shell. This infinitesimal volume should be multiplied by the density \(\rho\) to get mass. Next let's explore the total mass in terms of \(r\) since each particle only experiences a gravity once from the mass closer to the center than itself.

\[M=\frac{4}{3}\pi r^3 \rho\]

This also is logical because the total mass inside a shell is equal to the volume of that sphere times the density.

So, substituting in these new terms we get:

\[dU=-\frac{16G\pi^2 r^4 \rho^2 dr}{3}\]

Let's integrate from 0 to \(R\) since this is our radius' range.

\[-\frac{16G\pi^2 \rho^2}{3} \int^R_0 r^4 dr=-\frac{16G\pi^2 \rho^2}{15}r^5|^R_0=-\frac{16G\pi^2 \rho^2}{15}R^5\]

Next let's get \(\rho\) out of this expression. We know that it is density so:

\[\rho =\frac{M}{\frac{4}{3}\pi R^3}\]

Plugging this into our equation for \(U\) we get:

\[U=-\frac{16G\pi^2 (\frac{M}{\frac{4}{3}\pi R^3})^2}{15}R^5=-\frac{144GM^2pi^2R^5}{240pi^2R^6}\]

This mess simplifies beautifully to our answer:

\[\boxed{U=-\frac{3GM^2}{5R}}\]

This problem done in collaboration with G. Grell and S. Morrison.

Worksheet 8, Problem 1: Virial to Kepler

For a planet of mass m orbiting a star of mass M*, at a distance a, start with the Virial Theorem and derive Kepler’s Third Law of motion. Assume that m << M* Remember that since m is so small, the semimajor axis, which is formally a = ap +a* reduces to a = ap.

\(M\) is the Mass of the Star

\(m\) is the Mass of the Planet

\(a\) is the distance between the Planet and the Star

\(G=6.7\times 10^8 \frac{cm^3}{gs^2}\) is Newton's gravitational constant

\(P\) is the period of the Planet

\(K\) is Kinetic Energy

\(U\) is Gravity Potential Energy

\(v\) is the planet's velocity

First let's start with the virial theorem.

\[K=-\frac{1}{2}U\]

We also know that \(K=\frac{1}{2}mv^2\) and that \(U=-\frac{GmM}{a}\).

Therefore:

\[\frac{1}{2}mv^2=\frac{GmM}{2a}\]

We can cancel the 1/2 and m.

\[v^2=\frac{GM}{a}\]

We can cancel the 1/2 and m.

\[v^2=\frac{GM}{a}\]

A planet's period is the time it takes to travel all the way around the planet so, \(P=\frac{2\pi a}{v}\). We can rearrange this to say that \(v=\frac{2\pi a}{P}\).

Substituting this in for v we get:

\[\frac{4\pi^2 a^2}{P^2}=\frac{GM}{a}\]

Simplifying and solving for P, we get:

\[\frac{4\pi^2 a^3}{P^2}=GM\]

\[\boxed{P^2=\frac{4\pi^2 a^3}{GM}}\]

Which is Kepler's Third law of Planetary Motion.

This problem was solved in collaboration with G. Grell and S. Morrison.

Simplifying and solving for P, we get:

\[\frac{4\pi^2 a^3}{P^2}=GM\]

\[\boxed{P^2=\frac{4\pi^2 a^3}{GM}}\]

Which is Kepler's Third law of Planetary Motion.

This problem was solved in collaboration with G. Grell and S. Morrison.

Sunday, March 1, 2015

Quasars

In a previous post I mentioned quasars as part of binary systems, but what are they exactly?

Quasars are among the most energetic objects in the universe. They are supermassive black holes that are actively consuming matter and energy in an accretion disk. An accretion disk is a plane of matter that is superheated as it accelerates into the gravitational well of the black hole. This disk gives off incredible radiation as the matter is turned into energy by its gravitational plummet. In nuclear fission, a massive atom splits into smaller atoms, and about 0.1% of the mass is converted into energy. In nuclear fusion – a far superior process – almost 0.7% of the matter is converted into energy. Accretion boasts a 10% matter to energy conversion rate. This is 100 times more powerful than fission, and 14 times greater than fusion per unit of input mass. This absurd energy output is why quasars are among the most energetic objects in the sky with luminosities greater than 100 times the luminosity of the entire Milky Way.

In case this isn't cool enough already, an accretion disk can generate two relativistic jets of matter and energy that are dispelled along the axis of rotation. Black holes (and quasars by extension) usually emit a mixture of electrons, positrons, and radiation. The matter in these jets moves at relativistic speeds (95%–99% of the speed of light) and thus extremely high energies. The major proposals for the formation of these jets are Blandford-Znajek processes in which magnetic fields around the accretion disk oppose the black hole’s spin, and the Penrose mechanism. In the Penrose mechanism, a rotating black hole creates an area of rotating spacetime in which the black hole’s angular momentum can be spent to eject particles at relativistic velocities along the rotational axis. When the jet is viewed directly, (the jet is directed at or near the observer) the resulting phenomenon is a blazar. The relativistic effects of the jet amplify the observed luminosity of blazars directed toward the observer, and diminish the luminosity of those directed away from the observer.

One may ask why quasars are near impossible to find int he sky for an unassisted observer considering their immense energy output. This is because they are so far away that they experience massive redshifts shifting their radiation signals into radio waves. Their very name suggests this: QUAsi -StellAr Radio source = QUASAR.

Sine Quasars are so far away, they are useful for tracking the movements of "fixed" stars in the celestial sphere because the quasars are even more "fixed" than the foreground stars providing a freelance point for measuring interstellar movement.

Quasars are among the most energetic objects in the universe. They are supermassive black holes that are actively consuming matter and energy in an accretion disk. An accretion disk is a plane of matter that is superheated as it accelerates into the gravitational well of the black hole. This disk gives off incredible radiation as the matter is turned into energy by its gravitational plummet. In nuclear fission, a massive atom splits into smaller atoms, and about 0.1% of the mass is converted into energy. In nuclear fusion – a far superior process – almost 0.7% of the matter is converted into energy. Accretion boasts a 10% matter to energy conversion rate. This is 100 times more powerful than fission, and 14 times greater than fusion per unit of input mass. This absurd energy output is why quasars are among the most energetic objects in the sky with luminosities greater than 100 times the luminosity of the entire Milky Way.

In case this isn't cool enough already, an accretion disk can generate two relativistic jets of matter and energy that are dispelled along the axis of rotation. Black holes (and quasars by extension) usually emit a mixture of electrons, positrons, and radiation. The matter in these jets moves at relativistic speeds (95%–99% of the speed of light) and thus extremely high energies. The major proposals for the formation of these jets are Blandford-Znajek processes in which magnetic fields around the accretion disk oppose the black hole’s spin, and the Penrose mechanism. In the Penrose mechanism, a rotating black hole creates an area of rotating spacetime in which the black hole’s angular momentum can be spent to eject particles at relativistic velocities along the rotational axis. When the jet is viewed directly, (the jet is directed at or near the observer) the resulting phenomenon is a blazar. The relativistic effects of the jet amplify the observed luminosity of blazars directed toward the observer, and diminish the luminosity of those directed away from the observer.

One may ask why quasars are near impossible to find int he sky for an unassisted observer considering their immense energy output. This is because they are so far away that they experience massive redshifts shifting their radiation signals into radio waves. Their very name suggests this: QUAsi -StellAr Radio source = QUASAR.

Sine Quasars are so far away, they are useful for tracking the movements of "fixed" stars in the celestial sphere because the quasars are even more "fixed" than the foreground stars providing a freelance point for measuring interstellar movement.

As Lawrence M. Krauss says in his book The Physics of Star Trek, "you would not want to encounter one of these objects up close. The encounter would be fatal."

Worksheet 7, Problem 1: Hydrostatic Equilibrium

Consider the Earth’s atmosphere by assuming the constituent particles comprise an ideal gas, such that P “ nkBT , where n is the number density of particles (with units cm ́3), k “ 1.4ˆ10 ́16 erg K ́1 is the Boltzmann constant. We’ll use this ideal gas law in just a bit, but first

(a) Think of a small, cylindrical parcel of gas, with the axis running vertically in the Earth’s at- mosphere. The parcel sits a distance r from the Earth’s center, and the parcel’s size is defined by a height ∆r ! r and a circular cross-sectional area A (it’s okay to use r here, because it is an intrinsic property of the atmosphere). The parcel will feel pressure pushing up from gas below (Pup “ P prq) and down from above (Pdown “ P pr ` ∆rq).

(a) Think of a small, cylindrical parcel of gas, with the axis running vertically in the Earth’s at- mosphere. The parcel sits a distance r from the Earth’s center, and the parcel’s size is defined by a height ∆r ! r and a circular cross-sectional area A (it’s okay to use r here, because it is an intrinsic property of the atmosphere). The parcel will feel pressure pushing up from gas below (Pup “ P prq) and down from above (Pdown “ P pr ` ∆rq).

Make a drawing of this, and discuss the situation and the various physical parameters with your group.

(b) What other force will the parcel feel, assuming it has a density ρprq and the Earth has a mass MC?

(c) If the parcel is not moving, give a mathematical expression relating the various forces, remem- bering that force is a vector and pressure is a force per unit area.

(d) Give an expression for the gravitational acceleration, g, at at a distance r above the Earth’s center in terms of the physical variables of this situation.

(e) Show that

dP(r) “ ́gρprq (1) dr

This is the equation of hydrostatic equilibrium.

(f) Now go back to the ideal gas law described above. Derive an expression describing how the density of the Earth’s atmosphere varies with height, ρ(r)? (HINT: It may be useful to recall that dx{x “ d ln x.)

(g) Show that the height, H, over which the density falls off by an factor of 1{e is given by

H “ kT (2)

m ̄g

where m ̄ is the mean (average) mass of a gas particle. This is the “scale height.” First, check the units. Then do the math. Then make sure it makes physical sense, e.g. what do you think should happen when you increase m ̄ ? Finally, pat yourselves on the back for solving a first-order differential equation and finding a key physical result!

(h) What is the Earth’s scale height, HC? The mass of a proton is 1.7 ˆ 10 ́24 g, and the Earth’s atmosphere is mostly molecular nitrogen, N2, where atomic nitrogen has 7 protons, 7 neutrons.

(b) What other force will the parcel feel, assuming it has a density ρprq and the Earth has a mass MC?

(c) If the parcel is not moving, give a mathematical expression relating the various forces, remem- bering that force is a vector and pressure is a force per unit area.

(d) Give an expression for the gravitational acceleration, g, at at a distance r above the Earth’s center in terms of the physical variables of this situation.

(e) Show that

dP(r) “ ́gρprq (1) dr

This is the equation of hydrostatic equilibrium.

(f) Now go back to the ideal gas law described above. Derive an expression describing how the density of the Earth’s atmosphere varies with height, ρ(r)? (HINT: It may be useful to recall that dx{x “ d ln x.)

(g) Show that the height, H, over which the density falls off by an factor of 1{e is given by

H “ kT (2)

m ̄g

where m ̄ is the mean (average) mass of a gas particle. This is the “scale height.” First, check the units. Then do the math. Then make sure it makes physical sense, e.g. what do you think should happen when you increase m ̄ ? Finally, pat yourselves on the back for solving a first-order differential equation and finding a key physical result!

(h) What is the Earth’s scale height, HC? The mass of a proton is 1.7 ˆ 10 ́24 g, and the Earth’s atmosphere is mostly molecular nitrogen, N2, where atomic nitrogen has 7 protons, 7 neutrons.

Let's take it from the top:

(a) Think of a small, cylindrical parcel of gas, with the axis running vertically in the Earth’s at- mosphere. The parcel sits a distance r from the Earth’s center, and the parcel’s size is defined by a height ∆r ! r and a circular cross-sectional area A (it’s okay to use r here, because it is an intrinsic property of the atmosphere). The parcel will feel pressure pushing up from gas below (Pup “ P prq) and down from above (Pdown “ P pr ` ∆rq).

Make a drawing of this, and discuss the situation and the various physical parameters with your group.

\(P_{Up} \) is the pressure below the slice. \(P_{Down}\) is the pressure above the slice. \(\Delta r\) is the infinitesimal thickness of the slice. \(r\) is the height above the earth's surface.

(b) What other force will the parcel feel, assuming it has a density ρprq and the Earth has a mass MC?

The parcel will feel a force of gravity given by \(F_G=\rho (r) Ag\) where \(\rho (r)\) is the density of the gas a a function of distance from the Earth's surface and \(A\) is the area of the slice.

(c) If the parcel is not moving, give a mathematical expression relating the various forces, remem- bering that force is a vector and pressure is a force per unit area.

If the parcel is not moving then the sum of forces upon it equals zero. So:

\[F_{P_{Up}} = F_{P_{Down}} +F_g\]

(d) Give an expression for the gravitational acceleration, g, at a distance r above the Earth’s center in terms of the physical variables of this situation.

Newton's gravitational formula states that:

\[F_g=\frac{GM_{object}M_{Earth}}{r^2}\]

We also know that \(F_g=M_{object}g\) so:

\[g=\frac{GM_{Earth}}{r^2}\]

(e) Show that

dP(r)/r =-gp(r) dr

This is the equation of hydrostatic equilibrium.

dP(r)/r =-gp(r) dr

This is the equation of hydrostatic equilibrium.

The standard gauge pressure relation states that \(P=\rho gh\)

Substituting our expression for \(g\) into this equation gives us:

\[P(r)=\frac{GM_{Earth}}{r}\]

Taking the first derivative of this with respect to \(r\) yields:

\[\frac{dP(r)}{dr}=-\frac{GM_{Earth}\rho (r)}{r^2}\]

Substituting \(g\) back in gives:

\[\frac{dP(r)}{dr}=-g\rho (r)\]

(f) Now go back to the ideal gas law described above. Derive an expression describing how the density of the Earth’s atmosphere varies with height, ρ(r)?

Ideal gas law states that \(P=nk_b T\) where \(n\) is the number of particles per unit volume, \(k_b\) is the Boltzmann Constant which equals \(1.4\ times 10^{-16}erg/K\), and \(T\) is the temperature in degrees Kelvin.

We can modify this by introducing the term \(\overline{m}\) which will be the average mass of a particle to get it back in terms of \(\rho (r)\).

\[P=\frac{\rho (r)}{\overline{m}}k_b T\]

From above we know \(\frac{dP(r)}{dr}=-g\rho (r)\), so:

\[\frac{d\frac{\rho (r)}{\overline{m}}k_b T}{dr}=-g\rho (r)\]

\[\frac{d\rho (r)}{\rho (r)}=\frac{-g\overline{m}}{k_b T}dr\]

Integrating both sides yields:

\[ln(\rho (r))=\frac{-g\overline{m}r}{k_b T}\]

Integrating both sides yields:

\[ln(\rho (r))=\frac{-g\overline{m}r}{k_b T}\]

Solving for \(\rho (r)\) we get:

\[\boxed{\rho (r) = e^{\frac{-g\overline{m}r}{k_b T}}}\]

(g) Show that the height, H, over which the density falls off by an factor of 1/e is given by

H=kT/mg

where m ̄ is the mean (average) mass of a gas particle. This is the “scale height.” First, check the units. Then do the math. Then make sure it makes physical sense, e.g. what do you think should happen when you increase m ̄ ? Finally, pat yourselves on the back for solving a first-order differential equation and finding a key physical result!

This means that a height difference of H will cause pressure to change by a factor of 1/e. Let's test this.

\[\frac{1}{e} = e^{(\frac{-g\overline{m}r}{k_b T}-\frac{-g\overline{m}(r-H)}{k_b T})}\]

\[e^{-1} = e^{\frac{-g\overline{m}H}{k_b T}}\]

\[\boxed{\rho (r) = e^{\frac{-g\overline{m}r}{k_b T}}}\]

(g) Show that the height, H, over which the density falls off by an factor of 1/e is given by

H=kT/mg

where m ̄ is the mean (average) mass of a gas particle. This is the “scale height.” First, check the units. Then do the math. Then make sure it makes physical sense, e.g. what do you think should happen when you increase m ̄ ? Finally, pat yourselves on the back for solving a first-order differential equation and finding a key physical result!

This means that a height difference of H will cause pressure to change by a factor of 1/e. Let's test this.

\[\frac{1}{e} = e^{(\frac{-g\overline{m}r}{k_b T}-\frac{-g\overline{m}(r-H)}{k_b T})}\]

\[e^{-1} = e^{\frac{-g\overline{m}H}{k_b T}}\]

\[1=\frac{g\overline{m}H}{k_b T}\]

\[\boxed{H=\frac{k_b T}{g\overline{m}}}\]

(h) What is the Earth’s scale height, HC? The mass of a proton is 1.7 ˆ 10 ́24 g, and the Earth’s atmosphere is mostly molecular nitrogen, N2, where atomic nitrogen has 7 protons, 7 neutrons.

It's time to plug and chug.

It's time to plug and chug.

\[H=\frac{k_b T}{g\overline{m}}=\frac{(1.4\times 10^{-16}ergs/K) \times (273 K)}{(980cm/s^2)\times (1.7\times 10^{-24} g/atom) \times (28 atoms/particle)}=\boxed{8.2\times 10^5 cm}\]

I collaborated with G. Grell and S. Morrison on this problem.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)